RAGNAROK IS COMING!

____________

This is an English translation of an article by five Nordic scholars of religion published in the Danish newspaper Politiken on Sunday September 15. (Danish version here)

____________

Innumerable researchers have shown that humanity is quickly moving into a global climate crisis, the proportions of which exceed all other crises in history. The recent explosion in heat records, escalating melting of ice caps, and wildfires in the Arctic and Amazon are just the most recent signs that truly dystopian perspectives are becoming manifest reality.

Why has it come to this? We have known for decades how deadly the situation could become. Yet, the most powerful man in the world frequently denies the existence of the problem. Also here in Denmark the former chairman of the parliament recently labelled it “climate nonsense”.

Part of the explanation may be that it is difficult for us to relate to potential dangers that are somehow beyond our everyday reality. Our suggestion here is that we look into the deepest layers of our own culture and find the memory of climate change and its consequences. There is much to suggest that our ancestors had this knowledge. We have just forgotten it. It is acutely necessary that we start remembering again.

Because it is by no means the first time that we experience spectacular climate catastrophes here in the North, and testimonies of this can be found in the myths of our Heathen past. In the poem Vǫluspá—‘The Prophecy of the Seeress’—we find one of the strongest expressions of the Nordic religion. It is the immortal foretelling of Ragnarok as recounted by the Nordic vǫlva, a kind of female shaman. She tells of the darkness that comes when the wolf is let loose, when the tree of life burns, and when monstrous beings will run howling through the world as human social order collapses.

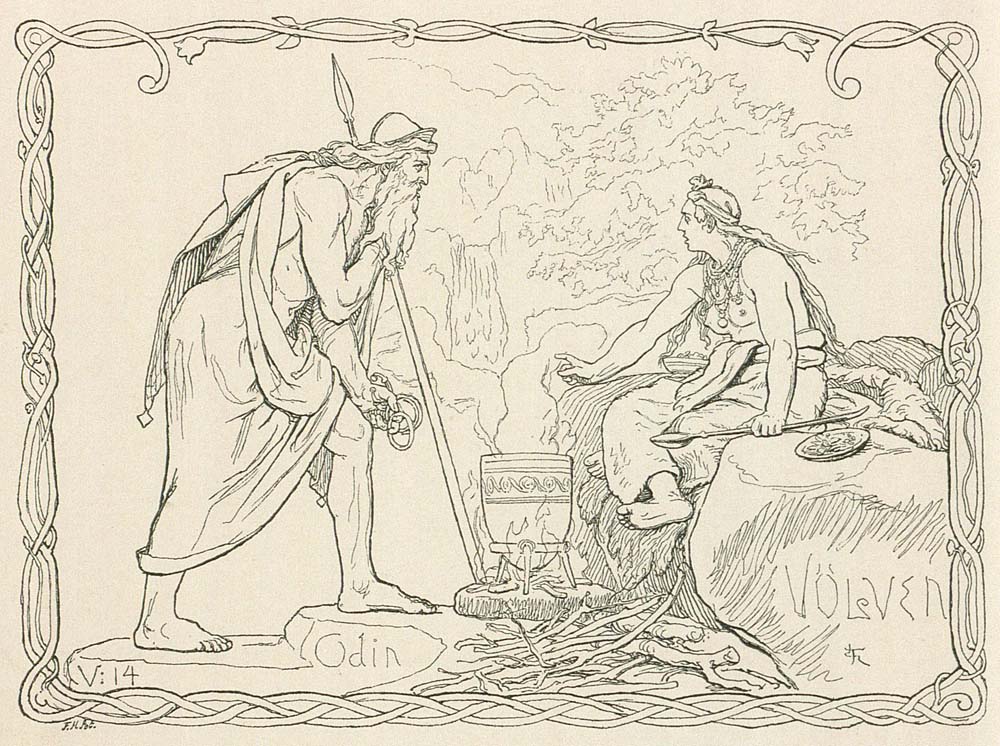

The god Odin receives the prophecy of the vǫlva (Lorenz Frølich Public Domain.)

The god Odin receives the prophecy of the vǫlva (Lorenz Frølich Public Domain.)There is a long tradition in research to see this mythic apocalypse in the context of climate changes in the Iron Age, and contemporary climate research seems to support this perspective.

Research in ice cores shows intense volcanic activity in the years 536 and 540. This supposedly caused climate change in Scandinavia in the 6th century. According to archeology professor Bo Gräslund, the occurrence of these events is supported by research in dendrochronology and written source material.

There was a cooling which was felt globally but which became particularly catastrophic in Scandinavia. Drawing from a mythic image in Vǫluspá, the researchers call this cooling “the Fimbul Winter”. In this period in the 6th century archeology shows a steep decline in human activity in Northern Europe. The population of Sweden was reduced by half. In Norway, farms disappeared and people abandoned cultural landscapes. Some areas became completely depopulated and the entire mass of archeological finds in Norway was reduced by 70-90% in this period. These are just numbers, but imagine what brutal realities must underlie these data—a 70-90% reduction in human activity! It must have been bloody and conflictual experience for the Nordic peoples, just as the Vǫluspá talks of violence and social collapse.

In the Vǫluspá the forces of harmony and chaos clash (Emil Doepler, Public Domain)

This period of decline is also visible in the Danish archeological record. In it, we find that settlements decrease or disappear, and cultural landscapes turn to forests. But there is also a noticeable increase in sacrifices of gold in the earth, which archeologists think may be a reaction to the “Fimbul winter”. Until December 2019 the Museum of Vejle in Jutland exhibits gold finds on the island of Hjarnø in 2018 under this theme. The thesis is that the extensive sacrifices of gold were an attempt to gain the favor of the gods following the climate changes and social collapse experienced in the 6th century.

If we wish to understand this, we must look at how the animist world view of the past strove to maintain balance in the world. Animism is the idea that the world is inhabited by gods and spirits which we must relate to in respectful ways and thereby create a mutually life-supporting relation between humanity and nature. The fields should grow. Livestock should be fertile. Humans should be healthy. The world should operate in a manner hospitable and beneficial to humans. This reciprocity rests on exchange. You give and then you receive.

When you harvest, you give a bit of the corn back to the earth, because the earth gave you the harvest. When you butcher an animal you give its blood to the gods so they can give life. In the archeological record, it is a clear indicator of the arrival of Christianity when people stop giving gifts to the dead. We find a steep decrease in valuable artifacts found in the ground. Clearly the god of Christianity is in the heavens, not in the Earth.

The 6th century "Fimbul Winter" is believed to be the cause of a remarkable increase in deposits of Iron age gold. (Arnold Mikkelsen, Nationalmuseet (CC BY-SA 2.0))

The old Nordic religion emphasized exchange that should maintain a friendly mutual balance and harmony between humans and the rest of the world. But in the 6th century, it must have been clear to people that this harmony had broken down. Something must have gone absolutely awry, because suddenly it didn’t really become summer.

It may be difficult for contemporary people to understand the extent of this catastrophe for a society based on subsistence farming. But the intense decrease in population and culture speaks very clearly: People of the 6th century desperately tried to remake the balance and the reciprocity. They gave the most precious possession they had, gold.

If we want to properly understand the Vǫluspá we also have to look at the cultural and social context of the poem.

The prophecy of Ragnarok as we know it today is composed in the late Viking Age (around 800 – 1050). It is shaped by a culture that experienced radical change. Today we tend to think of the Viking Age as a glorious time of conquest, filled with warrior spirit, energy, and strength. This is partly a romantic fantasy, yet it is also an image that reflects an important side of the Viking Age, aggressive globalization.

More generally, the Viking Age was characterized by ruptures and social change. Most people in the North probably experienced the period as unstable and disconcerting, an age where the traditional order of things became compromised. This was a period where Scandinavia went through intense processes of cultural and social change, urbanization, state formation, globalization and Christianization. It is probable that many felt that their world was out of order.

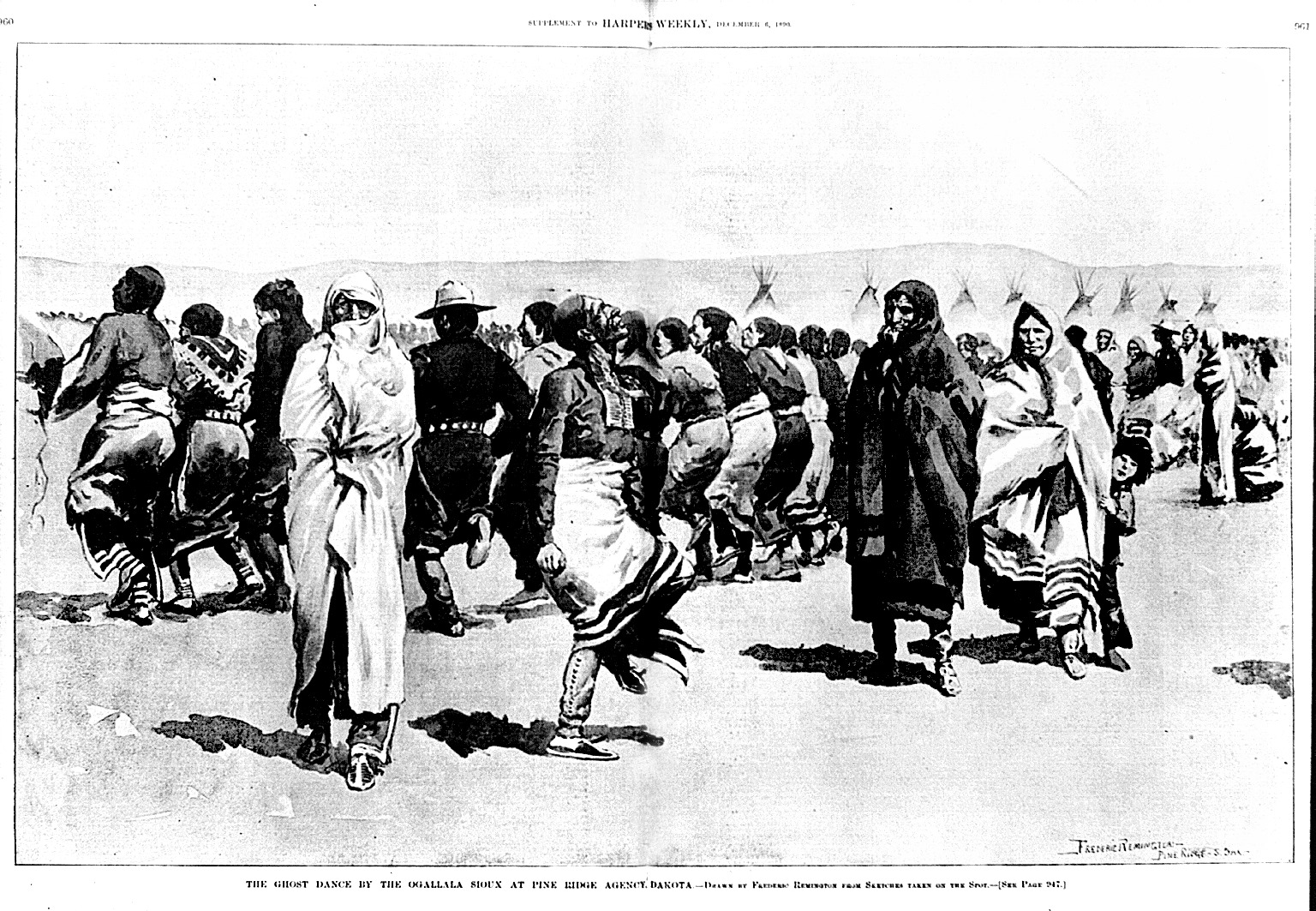

Apocalyptic beliefs are a well-documented result of this experience. Similar cultural expressions are found among indigenous peoples whose life and world view have been compromised by colonization. In such situations, myth and ritual serve as tools people use to analyze collapse and allow the impacted to harken back to the lost harmony of the known ordered world. In the study of religious history, this kind of reaction is called millenarianism.

The Native American Ghost Dance of 1890 is an example of a Millenarian Movement (Frederic Remington, Public Domain)

Such millenarianism and reflection about rupture is visible in the Nordic mythology, where it can be detected in 12th century historian Saxo Grammaticus’s “The Deeds of the Danes” (Latin Gesta Danorum), and traditional narratives about the mythic king Frode of Denmark, we find a powerful image of fatal consequences that ensue from the rupture between humans and the forces that run the world, such as in the eddic poem Grottasǫngr. Grottasǫngr tells how the legendary King Frode allowed his greed to supersede respect in his relations with two giant women, Fenja and Menja, primordial forces who drove a magic millstone and so produced the wealth and fortune of his kingdom. They punished him by causing the violent collapse of his kingdom.

The Vǫluspá can be seen as a kind of climate millenarianism. It is a mythic analysis of the social and environmental collapse as traditional animist culture was being compromised.

But what relevance does all of this have for us today?

It happens that we also live in a time marked by rupture and change. We witness growing social tensions, eroding values, and globalization. The social order that we know is changing, becoming more unsafe while inequality increases. We once trusted the decency of political leaders but today that trust is at a historical low, a phenomenon euphemistically called “the crisis of democracy”. At the same time we are passengers on a ship steering towards climate catastrophes of apocalyptic dimensions.

The seeress’s prophecy warns us. Even though the Vǫluspá was composed in a different age and is grounded in another time, it nonetheless invokes situations and circumstances that are very characteristic of today: Climate change, social collapse, and ruptured traditional culture.

In the Vǫluspá, we are looking into the eyes of a dark and violent chaos from a ship of globalized consumerism. While we grow ever closer to that grim future, our ancient culture teaches us what climate change can do to a society. The Viking Age seeress does not mince words, and that is exactly what we need if we are to wake up and relate responsibly to the escalating climate crisis.

Fortunately, all is not darkness. In the Vǫluspá, there are forces that fight for life and life itself will defy the cataclysm, a new and green world will rise from the waters.

There is today a fast growing green movement all over the world. More and more people are raising their collective voice. But we are still on the wrong track and there is a serious risk that our civilization will meet its Ragnarok if our present course continues.

That life on earth will continue is beyond doubt. What is uncertain is if it will include humans.

Vǫluspá; "She sees arise, a second time, earth from ocean, beauteously green, waterfalls descending; the eagle flying over, which in the fell captures fish" (Emil Doepler, Public Domain)

Jens-André P. Herbener, cand.mag., mag.art.

Mathias Valentin Nordvig, cand.mag., ph.d.

Benjamin Weber Pedersen, cand.mag., ph.d.-student.

Rune Hjarnø Rasmussen, cand.mag., ph.d.-student

Jane Skjoldli, cand.mag., ph.d.

____________________________________________

Full Image Attributions:

Title: part of the Gosforth Cross, showing some sort of double-monster and a humanoid figure

Author: Reproduction by Julius Magnus Petersen

Source: Photographed from Finnur Jónsson (1913). Goðafræði Norðmanna og Íslendinga eftir heimildum. Híð íslenska bókmentafjelag, Reykjavík. Page 99.

- https://upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/f/fc/Gosforth_Cross_monsters.jpg

License Public Domain

Title: Odin og Vølven

Author: Lorenz Frølich

Source: Det kongelige Bibliotek - https://upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/a/ab/Lorenz_Froelich-tegning.jpg

License Public Domain

Title: Odin und Fenriswolf Freyr und Surt.

Author: Emil Doepler

Source: Walhall, die Götterwelt der Germanen. Martin Oldenbourg, Berlin. Page 55.- https://upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/a/aa/Odin_und_Fenriswolf_Freyr_und_Surt.jpg

License Public Domain

Title: Brakteater, Jørlunde/Hjørlunde.

Author: Arnold Mikkelsen

Source: Nationalmuseet, Danmark

LicenseAttribution-ShareAlike 2.0 Generic (CC BY-SA 2.0) - https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-sa/2.0/

Title: Ghost dance by the Oglala Lakota at Pine Ridge

Author: Frederic Remington

Source: Library of Congress - https://upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/1/13/Ghost_Dance_at_Pine_Ridge.png

License Public Domain

Title: after Ragnarök

Author: Emil Doepler

Source: Walhall, die Götterwelt der Germanen. Martin Oldenbourg, Berlin. Page 58.– https://upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/f/f2/After_Ragnarök_by_Doepler.jpg

License Public Domain